The rise in gardening to heal communities

The Community Greening program has established hundreds of community gardens across New South Wales to positively impact people in cities and remote communities

A transitory haven

In Brookvale, a suburb located on Sydney’s lower North Shore, people facing unemployment, mental health issues and severe hardship occupy a crisis accommodation centre. The red brick dwelling hosts 25 self-contained rooms that see newcomers arrive every three to six months. Supported by Mission Australia, the centre functions as a temporary haven for trauma recovery, helping people transition into more permanent housing.

Within the centre’s communal outdoor areas lies a leafy sustainable garden, where occupants tend to plants, grow fruits and vegetables and feed roaming chickens. The Botanic Gardens of Sydney’s Community Greening program has been at the heart of it, helping the community to engage with their outdoor space and reconnect with nature. As rental prices climb and more occupants (including employed families) seek support, the need for these vital spaces is increasing.

Community Greening has built hundreds of gardens across NSW to help vulnerable communities.

Over 20 years helping communities grow

The Community Greening program has worked for over 23 years with people living in social housing across New South Wales to help them grow community gardens and green spaces, thanks to funding from Department of Communities and Justice and MetLife.

The program’s reach extends far beyond city areas – dedicated horticulture and education experts work across Aboriginal communities in regional areas and out in some of the most remote parts of the state. Each garden that is created is co-designed and co-built with the community, tailoring it to their needs it and the climate of the area.

“There’s nothing that can explain the reward of going out and picking something from your own garden, even it’s if only herbs. You feel so relaxed and then you feel that satisfaction that I have done something for myself.” – Community member

A communal garden can create a huge impact to a small group, a regional or town or city. This year alone Community Greening has transformed over 600 gardens across the state and seen both the immediate and long-term benefits for vulnerable communities. Building these tranquil spaces and educating people on horticultural practices provides fresh food and relaxing spaces to occupy, while forming a social and therapeutic outlet and place for people to connect.

Over 1100 programs and 212,700 youth and community participants have been involved in Community Greening projects since it began in 2000. Whether it’s working with people from refugee, Indigenous, culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds - most enjoy the sense of satisfaction and reward created by the space.

“Community gardens give people a new ability to grow their own food and flowers, it brightens ups their homes and I’ve witnessed first-hand how it empowers them to be in charge and in control of their own space.” - Phil Pettitt

Creating successful sustainable gardens

In the North Shore crisis centre, the Community Greening team set out to have an accessible, sustainable, and practical space where anyone can tend to the beds and the life of each plant can be prolonged.

Each material used and plant grown has a purpose: the wicking garden beds save water use and help the plants survive longer. The beds sit at a higher level to enhance access. The walls are made from recycled pallets to define the space and keep it secure from the clucky chickens that surround the area. The chickens help to recycle food scraps from the housing, and they feed the families breakfast - creating a continuous, harmonious cycle.

Occupants and local volunteers at the Garden have completely embraced the space as a place for both mental recovery and food production. Almost every kind of vegetable and fruit can be grown here, from small Asian greens like mizuna to tall lemon trees that fruit in the yard.

The team have also introduced a hive of native stingless bees to increase the pollination of plants. When they plant cucumbers, they'll get more flowers, and even more fruits will form. People can experience the bees coming in and out of their hive and experience the satisfying cycle of plants pollinating, seeding and growing.

Located on Ansen Street, the Bourke Community Garden is now open to the public. Credit: UNSW

Reaching far-out places

About 800km north-west of Sydney on the Darling River lies Bourke, a town known as the doorstep to outback Australia. The classic slang term ‘Back o Bourke’, meaning far away, refers to the endless desert stretching from the region’s west.

It’s no wonder then, that this cross section of red dirt and bushland filled with sprawling native trees and a flowing river has some locals with serious green thumbs.

Last year, the Community Greening team ventured out to the remote town to transform its 20-year-old community garden, as part of a partnership between REDIE, the Bourke Aboriginal Corporation Health Service (BACHS), the North West Academic Centre and the University of NSW Faculty of Arts, Design and Architecture.

When the teams first arrived at the garden on the town’s south side on Ansen Street, it was heaving with overgrown weeds, dishevelled wooden beds and piles of dead leaves. As the teams gathered, locals immediately dived into to help reinvigorate the space, using their knowledge of the area’s climate and flora.

After months of planning and preparation, both locals and teams began building and gardening. New nets and structures were installed to overlay the plants, and the old wooden beds were replaced with fresh tin lining, resurrecting the bones of the acre. The teams and locals sowed almost everything - vegetables, fruits, native plants, herbs and flowers.

A year on, the garden is now a thriving epicentre for locals to share knowledge, harvest, and learn more about gardening for their own homes and spaces. Landscape architecture students from UNSW still contribute to parts of the garden, helping to expand and grow the area. It is now an oasis, creating a cool place in the dry heat of summer and providing seasonal food all year round.

Community Greening teams and locals worked to reinvigorate the space. Credit: Botanic Gardens of Sydney

Delivering greener urban spaces

The community housing in Sydney’s city suburb of Woolloomooloo is nestled in a blonde brick dwelling on Forbes Street. Its recent green-up has seen planters and colourful garden beds installed to grow lush flowers and fruit.

Edith Blaise from MetLife, the Garden’s principal partner, visited the garden to join local volunteers who regularly weed and prune its produce.

“The garden beautifies the strip with its thick greenery and colourful flowers,” said Edith.

“It gets the community together while its vegetables and fruit produce are used in the local community café.”

“Gardening is a calming and relaxing pastime and it’s a just bonus to enjoy the aesthetics, and if all goes well, even a harvest! This time we were lucky to pull out chilies, tomatoes, eggplants, zucchini, basil and beans.”

“MetLife is committed to drive a positive impact on the world around us. We encourage our employees to take one day of volunteer leave to get into their local community and connect.”

: L-R: Phil Pettit with local community Gardener Nanita and Metlife Volunteers at the Forbes Street Wooloomolooo community garden. Credit: Botanic Gardens of Sydney .

The future of communities

As more families face hardships and seek support, the importance of building and maintaining these flourishing spaces for communities to reconnect is vital. Community Greening gardens offer not only means of affordable food production but are a place of refuge for those seeking to reconnect with the community and themselves.

Over two decades, Community Greening has created a legacy of helping people build practical skills, confidence, and purpose to thousands of people. With hundreds more gardens to tend to and thousands of communities in need of restoring connection, using gardening as a means of engagement is a sure-fire way to empower many.

“There’s a positive feeling. A lot of them some sort of anxiety or depression or loneliness, and it’s really nice to get together and share and work in the garden.” – Community member

Related stories

An easy, beginner-friendly guide to transform your backyard or balcony into a dreamy, native meadow inspired by Australian flora and the sleepy charm of blue‑banded bees.

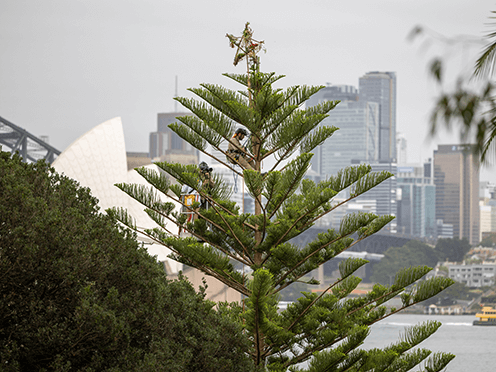

Discover the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney's very own "Christmas trees" - a festive trio of pretty pines from a lineage stretching all the way back to the time of the dinosaurs.

An extraordinary display of rare turquoise blooms are starting to flower at the Blue Mountains Botanic Garden Mount Tomah, with one species blooming for the first time ever.