Biosecurity

Biohazards are the endemic and exotic pests, diseases and weeds that affect Australia’s plant industries, community and environment. Biosecurity protects our plant resources for future generations.

Rose Aphids

Rose Aphids

The sap-feeding enemy of the Rose

Species:Macrosiphum rosae

Aphids are small, soft-bodied insects that are members of the insect order Hemiptera which also includes psyllids, cicadas, leafhoppers and bed bugs.

Macrosiphum rosae is one of the thousands of aphid species found globally. It’s host-specific, which means it feeds only on or in one species. This Aphid has a penchant for feeding on the sap of rose shoots, tips, and buds. Rose Aphids suck up nutrients from rose plants which damage their foliage and flowers.

Aphid secretions cause Sooty Mould!

The damage to the Rose doesn’t stop there; the insect’s secretions, also known as Honeydew, cause a secondary disease, Sooty Mould. Sooty Mould disrupts the plant’s photosynthesis and respiration. Aphids also spread other diseases as they move from plant to plant. They are most active during spring and summer when tender rose shoots and buds grow.

Macrosiphum is derived from the Greek ‘macro’ meaning large and the Latin ‘Sipho’ meaning siphon, both of which reference the Aphid’s siphoning mouthparts that suck up their host’s sap. Rosae has its origin in the Latin for Rose, rosy or pink.

Australian records have mapped aphids along the east coast, Victoria, South Australia, New South Wales, the ACT, and Western Australia. The Aphid’s spread is via infected plant matter, which can travel hundreds of kilometres. They reproduce asexually and give birth to live young, so preventing their spread may seem like an uphill battle for the home gardener.

Of the 5000 known aphid species, only a few dozen are Australian natives. Most of the aphids in our gardens are descended from insects that piggy-backed their way here on cultivated plants.

Aphids damage rose blooms, which causes losses for industry, home gardeners and ornamental growers, it is tough to prevent the spread of rose aphids because they can fly.

Deadheading flowers, regular pruning, and regular fertilising and watering can reduce the prevalence of aphids in your rose garden. Hand removal is also an option for home gardeners. Gardeners at The Royal Botanic Garden Sydney have had success with the introduction of predatory insects and changes to their cultural practices. A number of years ago we introduced a parasitic wasp (Aphidius rosae) which lays its eggs inside the aphid. When the egg hatches the larvae of the wasp eat the aphid from the inside! Look out for affected aphids which are tan-coloured, swollen and mummified on roses – a great sign that biological control has been effective.

Chemical control of aphids is considered a last resort because it harms bees, ladybirds and other beneficial insects.

The Royal Botanic Garden Sydney’s Palace Rose Garden has yearly problems with aphid infestation.

Ants and Aphids

Garden Sign Story – Rose Aphids

These tiny, soft-bodied bugs can migrate hundreds of kilometres, and have offspring at a rate of 12 per day!

Image caption: In a hurry to reproduce, aphids can lay eggs or give birth to live young.

Photo: C. Quintin FLICKR CC BY-NC 2.0

War of the roses

Aphids are a gardener’s nightmare. They reproduce in the millions, all busy slurping sap from buds and new shoots with their straw-shaped mouthparts.

But we’ve got good insects on our side! Lacewings, Ladybug and Hoverfly larvae are released into the Garden to munch on aphids. Another helpful predator, parasitic wasps (Aphidiius rosae) lay their eggs inside aphids. The wasp larvae hatch and eat the aphid from the inside out.

Image caption: Look closely to find the bodies of parasitised aphids — sometimes you can see where the wasp emerged from the host.

Photo: M.Yokoyama FLICKR CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Having babies

Aphids never stop multiplying. Two remarkable methods are parthenogenesis — where females bypass the need to mate and give birth to clones. And paedogenesis — where juvenile aphids are born pregnant!

Armillaria luteobubalina

Armillaria luteobubalina

Armillaria luteobubalina – Honey Fungus

Armillaria is a genus of plant pathogens that are found worldwide and includes the parasitic fungi Armillaria luteobubalina.

There's nothing sweet about Honey Fungus

Also known as Australian Honey Fungus, Armillaria luteobubalina, is a native fungus that causes the disease Armillaria root rot. Root rot is a significant cause of tree death and forest dieback; it infects many plants, including Australian natives.

Armillaria luteobubalina feeds on live tissue, and on dead and decaying wood. While most of the Root Rot is located underground, and in the water transport systems of the trees it has infected, it can spread some way up the trunk of a tree.

Armillaria is initially hard to detect because its mycelia are below the ground; it can take years before its symptoms are visible; when it’s fruiting in May-June, olive-brown mushrooms appear.

Armillaria Root Rot is hard to control, and there is no cure once it is established. Infected plants should never be moved or composted; we recommend instead that you put infected plant matter in the hard rubbish after letting it dry in the sun to prevent it from spreading in your garden.

Root rot – prevention is better than cure

Ensuring you don’t bring infected plants into your garden is the most effective prevention.

Armillaria is derived from the Latin armilla, ‘bracelet,’ which refers to the frill on the fungi’s fruiting body, which resembles a bracelet. Luteobubalina refers to the olive, yellow colour of the mushroom (luteo) and the shape of the mushroom.

Often appearing on the trunks of decaying trees, Armillaria thrives in wet, moist environments.

Armillaria’s fruiting body is the mushroom; the stalk can be up to 15 cm tall and the cap up to 12 cm across. When mature, its spores spread far and wide on the breeze, although it is very rare for new infections to start from spores.

Yes, Armillaria is present across the Garden; the Royal Botanic Garden arborists find its fruiting bodies as winter approaches.

Garden Sign Story – Armillaria

A parasite lurks just out of sight. Growing ever larger, it feeds… draining this tree’s life away.

Hidden infection

It can be hard to spot, but if you look at this tree’s lower trunk, you can see lesions – a tell-tale sign of Root Rot (Armillaria luteobubalina). These have been spreading slowly since around 2017.

Armillaria fungi live as large underground webs of hyphae – root-like structures. They feed on roots and invade the host trees, feeding on living and dead plant material. Once infected, a tree cannot be saved.

Image caption: In May and June you can see the fungal fruiting bodies growing up the trunk.

Photo: B. Summerell

Canna Rust

Canna Rust

Canna Indica’s enemy – Puccinia thaliae

Puccinia thaliae is a fungal pathogen that causes brown spots known as Canna Rust on Canna indica (Canna lilies), a popular floral display plant with colourful blooms.

Canna Rust occurs all over Canna leaves but is most prominent on the underside, eventually cloaking the entire leaf. The spots on the upper leaves eventually turn brown/black, and holes develop in older leaves. Finally, they become dry, wilt and fall.

In addition to travelling on the breeze and in water, Canna Rust’s spores spread on tools or boots. The fungi are host-specific, and although there is no cure for it, removing and burning infected foliage to prevent its spread is a sustainable way of controlling it. Never compost the cut foliage because it will spread the fungi.

A drench with fungicides will maintain the ornamental value of your planting, and copper products will kill the spores. Ensure that both the upper and lower leaf surfaces are covered.

Growing resistant or semi-resistant Canna cultivars is one of the easiest ways to prevent Puccinia thaliae. Healthy plants are less vulnerable to Rust, and feeding and mulching them is recommended.

Cutting back your Canna Lilies seasonally will encourage new growth, which can be treated at the onset of infection.

If you plant your Cannas in full sun and drip-irrigate them, it will also help control the Rust; overhead watering can spread spores from the plant to the soil.

Roya de la canna de Indias (Spanish)

Rouille du balisier (French)

Puccinia thaliae was named to honour Tommaso Puccini, an Italian anatomist. Thaliae, is derived from the Greek word ‘thaleia’, which means ‘blooming’ or ‘bounteous’ and refers to Canna Rust’s abundance of spores.

Canna Rust occurs wherever Canna Lilies are grown; it is tough to control because its spores are so prolific. It is the ultimate globetrotter and can travel thousands of kilometres on the breeze, as well as being able to float on water.

Canna Rust thrives where there is high humidity and long periods with wet foliage (roughly ≥20°C). High soil moisture, tall weeds growing around the plants and dense shade that prevents water from evaporating all combine to create an ideal environment for the fungi to grow. Sydney’s warm, humid summers are Canna Rust’s perfect climate.

Rust fungi have many spores, some with resistant cell walls that survive without a host plant. They germinate later and produce other spore types, continuing the fungi’s life cycle.

The Garden’s collections include hybrids and variegated varieties. There are extensive beds of ornamental plantings across the Garden, including the variegated variety Canna ‘Stuttgart’.

Visit the Garden Explorer and type 'Canna 'Stuttgart' into the 'Common or Scientific Name' field, then click 'search' to be shown where to find it.

Garden Sign Story – Canna Rust

Rust is a super-parasite. Billions of tiny fungal spores can travel for thousands of kilometres to find their next victims.

Control, not cure

There’s no cure for Canna Rust (Puccinia thaliae). Instead, the Garden’s Horticulture Team use control measures:

We choose canna varieties that are rust-resistant.

Cannas are planted in full sun and spaced to create airflow around the plants.

We water at soil level, to keep the leaves dry.

Healthy plants are stronger, so we provide extra nutrients and mulch.

Infected leaves are removed, and we cut the plants to the ground in autumn.

Image caption: Lines of rust pustules erupt parallel to the leaf veins on Canna indica.

Photo: S. Nelson FLICKR

Rust fungi infect plants through the stomata – leaf pores. Once inside, they steal nutrients, growing ever larger while starving the plant.

Image caption: Photo: Cesar Calderon, Pathology Collection, USDA APHIS PPQ, Bugwood.org CC 30.0

The Gardens' Arborists regularly check the Moreton Bay Figs in the Gardens for Fig Psyllids

Fig Psyllids

Fig Psyllids – Mycopsylla fici

Psyllids are a group of sap-feeding insects related to aphids and scale insects that can spread bacterial infections and damage many plant species.

Scale insects love to dine on Morton Bay Figs

Psyllids are fussy eaters and only feed on specific species of host plants. The fig psyllid Mycopsylla fici favours the Moreton Bay Fig, Ficus macrophylla. There are many mature, magnificent specimens throughout the gardens, and arborists regularly check them to assess the damage and treat it.

Fig Psyllid

Lerp

Fici is derived from 'ficus', Latin for figs or fig trees and the Italian word fico, which means 'a fig'.

Mycopsylla fici occurs in Australia, New Zealand, and Lord Howe Island. It can fly and quickly moves from its host fig tree to others once it’s established in parks and gardens.

Several Psyllid life cycles can occur in a year; flying adult females lay clusters of rusty brown-coloured eggs on the underside of leaves and the eggs hatch into white nymphs.

Climate change may make Scale Insects more common

Psyllid outbreaks are more likely to be catastrophic in drought-affected trees, when the weather is hot and dry, and these conditions may become more common as our climate changes.

Sound tree management practices are the best way to control outbreaks of fig psyllids. Mulching fallen leaves offers protection to tree roots and encourages natural predators, including wasps, birds and small mammals.

There has been success combatting the fig psyllid with a naturally occurring parasitic wasp. The wasp lays eggs in the psyllid’s soft body, and hatchlings feast on the psyllids from the inside out. Mulching the leaves encourages the build-up of numbers of the wasp.

There are two species of Mycopsylla psyllid that affect fig trees in Australia. M. fici feeds on the Moreton Bay Fig (F. macrophylla) and Mycopsylla proxima feeds on the Port Jackson Fig (Ficus rubiginosa). Both trees are found across our Gardens’ living collections and have been damaged over the years by psyllids.

Visit the Garden Explorer to find Moreton Bay and Port Jackson Figs in the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney, Australian Botanic Garden Mount Annan, Blue Mountains Botanic Garden Mount Tomah.

Fig Psyllid (mycopsylla fici)

Garden Sign Story – Fig Psyllids

Feeling itchy? This tree has lice! Look closely and you might see the infestation of tiny sap-sucking insects.

Unwelcome guests

Fig Psyllids (Mycopsylla fici) live out their full life cycle on the host tree. Hatching from tiny eggs on the leaf-edges, the nymphs suck sap from the leaves as they develop into winged adults.

Healthy figs can cope with some leaf-loss, but psyllid numbers increase in dry, hot weather. Over time, trees can suffer die-back and death. We carefully maintain the fig’s water and nutrient levels. Keeping fallen leaves protects tree-roots and encourages natural psyllid predators.

Sugar-house snacks

Each soft-bodied psyllid nymph excretes sugar which crystalises, forming a lerp – a protective cover. These are a tasty treat for many birds and small mammals.

Cavendish Bananas

Fusarium Wilt of bananas

Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. cubense

Fusarium Wilt is a vascular wilt disease; it attacks a plant’s vascular tissues, which contain water, nutrients and sap. The common fungal soil-borne pathogen that causes Fusarium Wilt in plants is Fusarium oxysporum, different plant species are susceptible to different strains of Fusarium.

One of the many strains is Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. cubense which causes Panama Disease, is host-specific, growing only on bananas and is one of the most destructive diseases in banana crops globally.

Panama Disease is incurable

Fusarium Wilt was the first banana-specific disease to spread worldwide in the first half of the 20th century. The epidemic began in Central America on ‘Gros Michel’, a variety that dominated the global banana export trade. It had no cure; however, a resistant cultivar 'Cavendish' was discovered and replaced Gros Michel all over the world wherever bananas are grown.

Growers can no longer save their skins with Cavendish Bananas

In the past, Australian growers relied on Fusarium Wilt resistant cultivars such as the Cavendish Banana to avoid financial and crop losses due to Panama disease. Unfortunately a new strain of the fungus 'Tropical Race 4' has evolved to attack Cavendish bananas and is now spreading around the world threatening banana production. The race is on now to discover disease-resistant cultivars to replace Cavendish bananas.

Panama disease of banana

Fusarium wilt

Fusarium is derived from the Latin 'fusus', meaning a spindle, which references the shape of the microscopic spore of the fungus.

'Oxus' is from the Ancient Greek word for sharp and 'sporos' for seed. 'Cubense' tells us that it comes from Cuba.

f. sp. (forma specialis) indicates that this is a special form of the pathogen. Botanists use this fungi naming protocol to distinguish between different, usually pathogenic, fungal strains.

F. oxysporum f.sp. cubense first appeared in the Americas, Africa and the Far East during the 1900s. It was detected around 50 years ago in South East Asia and has spread to the greater Mekong subregion and Australia. More recently, it was found in India, Pakistan, Oman and Mozambique and was identified in Colombia in 2019.

Fusarium species can produce up to five propagation methods, including four types of spores that have different functions.

A banana plant with Fusarium Wilt

Garden Sign Story – Fusarium Wilt

Australians eat five million bananas daily! One of the world’s biggest crops, bananas have been fighting disease since the 1950s.

Image caption: Biosecurity measures at banana plantation in Queensland.

Photo: Karegg - Shutterstock

Banana battles

Since the 1950s, Panama Disease has caused devastating banana crop losses around the world. The disease is caused by Fusarium fungi – super-parasites that survive fungicides, fumigation and soil sterilisation.

Cavendish bananas were introduced to Australia because they were resistant to the disease, but the fungus has evolved. Now, outbreaks are managed by strict quarantine and the destruction of infected plants. Our best hope is to develop new, resistant banana varieties.

Image caption: A cross-section of an infected banana stem shows how the fungus liquifies the plant from the inside.

Photo: S. Nelson - FLICKR

Clone consequences

Banana crops are clones, grown from root divisions rather than seed. They are genetically identical – making them particularly vulnerable to disease.

Myrtle Rust

Myrtle Rust

A threat to the endangered Myrtle Lenwebbia sp. Main Range

Lenwebbia sp. Main Range is a critically endangered endemic member of the Myrtaceae family of plants – the family also includes eucalypts, paperbarks and lillypillies. Small in stature, it grows to 4 metres in height, has brownish fibrous bark, branches that are densely covered in short hairs, and glossy green oval-shaped leaves. Like many of the Myrtle family, It is threatened by the exotic rust fungus Austropuccinia psidii.

First Nations uses of the Myrtaceae family

First Nations Peoples have used members of the Myrtaceae family as plant medicines, bush foods and building materials for thousands of years.

Lenwebbia, was named for the Australian plant ecologist Dr Leonard Webb who worked as a research scientist at the CSIRO Rainforest Ecology Section.

Main Range – is a reference to the Main Range National Park in South East Queensland, where this species is found.

Lenwebbia Main Range is found at 900-1200 metres above sea level in rainforest vegetation on and around the New South Wales – Queensland border. It grows on rocky outcrops along exposed escarpment cliff lines and steep slopes in volcanic soils with south-facing exposed aspects.

Lenwebbia’s white flowers are either solitary or grow in threes; after flowering it produces black berries that are 5-7 mm in diameter.

There are no specimens of Lenwebbia sp. Main Range at the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney or Blue Mountains Botanic Garden Mount Tomah.

A related species can be found at the Australian Botanic Garden Mount Annan: Lenwebbia prominens often co-occurs with Lenwebbia sp. Main Range but has larger flowers, leaves, and fruits.

There are a number in the nursery at the Australian Botanic Garden Mount Annan as part of a rescue population to ensure its survival.

Lenwebbia Prominens

Garden Sign Story – Myrtle Rust

Like families, friends and workmates: Communities of plants, animals and fungi interact, compete, protect and support each other.

A sheltered life

Australia is an island. Separated from other land masses for millions of years, unique life forms evolved together – creating one of the most biologically diverse places on the planet. Unfortunately, this isolation has also made Australian plants vulnerable to exotic diseases like Myrtle Rust.

Three-quarters of Australia’s forests are dominated by gum trees and other members of the Eucalypt family, and they are under attack. Losing our Eucalypts would change Australia forever.

Caption: Myrtle Rust has pushed some species to the brink of extinction. (Lenwebbia sp. Main Range).

Photo: G. Phillips.

What the Flora!? A Plant Pandemic

Did you know that our native species are battling a plant pandemic? Listen to the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney's podcast to learn more about how Myrtle rust is pushing the Myrtle family to extinction and threatening the survival of our ecosystems.

A Brown Marmorated Stink Bug

Brown Marmorated Stink Bug

Halyomorpha halys

A relative of the aphid, the Brown Marmorated Stink Bug is a member of the order Hemiptera and the Family Pentatomidae.

Description

The Brown Marmorated Stink Bug is a significant destructor of crops, which has economic and social impacts. Like aphids, they are sap-sucking insects with piercing mouthparts, although they are not host-specific and feed on over 100 different plant species.

The bug injects saliva into the fruit it feeds on, depleting its hosts of nutrients and causing them to rot. It infests many economic crops and spreads rapidly by flying up to a few kilometres a day. It has no natural enemies when it reaches new environments, which enables it to cause devastating infestations.

Are there stink bugs in Australia?

Biosecurity experts have several times intercepted the Brown Marmorated Stink Bug in cargo at border control. Although it occurs in many regions worldwide, it is not in Australia.

Many predator and parasitoid species can attack the Brown Marmorated Stink Bug in its native and invaded habitats, including wasp species.

Halyomorpha – is derived from the Latin ‘halare’, which means ‘to be fragrant’ or ‘emit vapour’, which references the stench the bug emits when touched.

The colouring of the bug is referenced by ‘marmorated’ from the Latin ‘marmoreus’, which means ‘of marble’.

The Brown Marmorated Stink Bug is native to North East Asian regions (China, Japan, Korea and Taiwan) and is an occasional and sporadic pest. It affects many crops, including apples, peaches, apricots, corn, grapes and tomatoes. Its spread through North America and Europe, South America, and New Zealand has led to its categorisation as invasive.

Garden Sign Story – Brown Marmorated Stink Bug

These bugs don’t just smell; they’ve got nasty table manners! They inject saliva into fruit as they feed, causing it to rot.

Image caption: Adult and nymph BMSBs use their needle-like mouthparts to pierce an apple.

Photo: US Dept of Agriculture FLICKR CC BY 2.0

Big bug attack

Brown Marmorated Stink Bugs (BMSB) are on the march. From Asia, they spread to Europe and the Americas and invaded New Zealand. They’re a top priority for Australian biosecurity – they’ve already been stopped at the border several times.

BMSBs are a serious threat to food production. They feed on crop plants including apples, corn and tomatoes. They’re resistant to insecticides and have no natural predators in Australia. Be on the lookout!

Image caption: You can help: If you spot a BMSB, take photos, capture it if possible, and call the Exotic Plant Pest Hotline: 1800 084 881.

Photo: David R. Lance, USDA APHIS PPQ, Bugwood Org.

Stench defence

No one wants to be eaten. Predators and people be warned – whenever Stink Bugs feel threatened, they spray putrid chemicals from holes in their abdomen.

Water Moulds and Downy Mildew

Peronosporaceae, a family of Water Moulds and Downy Mildew

Peronosporaceae is a family of water moulds with more than 600 species, most of which are downy mildews. The Phytophthora species threaten native ecosystems as well as agricultural and horticultural crops.

Phytophthora spread via spores through waterways and soil, which can then be mechanically spread via shoes, tent pegs, gardening tools, and bike and car tyres. It has a wide host range (over 1000 species), and once introduced into an area it can exist on the roots of many different plants, sometimes without causing visible symptoms on the foliage.

Aotearoa's (New Zealand) native Kauri tree (Agathis Australis)

Kauri Dieback

Phytophthora agathidicida

Agathis australis, the Araucariaceae that towers above all others

Phytophthora agathidicida is a plant pathogen named for the tree species it attacks, the Kauri Pine (Agathis australis).

The Kauri is a magnificent coniferous tree, towering over its neighbours in the forests of the northern North Island of Aotearoa (New Zealand), often reaching heights of 40-50 metres tall. It is a member of an ancient Gondwanan plant family that goes back 175 million years in the fossil record.

First Nations' uses of Kauri

Māori Peoples consider Kauri to be ‘taonga' – treasures of great significance.

Māori had many uses for kāpia (Kauri gum) they made gum torches and Kauri ash was mixed with oil and fat and then used to colour moko (facial tattoos). It was also an ingredient in chewing gum. In the early years of European colonisation, Kauri gum was exported in large quantities as a varnish.

Phytophthora is derived from the Greek word ‘Phyto’, meaning plant, and ‘phthora’, which means to decay, ruin or perish.

The species name, agathidicida references Agathis, the tree genus affected by the water-borne pathogen.

Agathis is the Greek word for a ‘ball of twine, which refers to the shape of the tree’s male pinecones.

‘Cida’ is derived from the Latin for strike or kill, hence – ‘kills Agathis’.

Kauri Agathis Australis with Kauri Dieback

Garden Sign Story – Kauri Dieback

Giants of the forest, New Zealand’s Kauri Pines can stand for two thousand years. Now they’re under attack… and falling.

Giants are falling

In 2006, a virulent new strain of the deadly water mould (Phytophthora agathidicida) was found in New Zealand. Spread by the movement of people and animals through the forests, it only attacks Kauri Pines, causing dieback and death.

If the disease reaches Australia, Kauris across the country will be vulnerable. There’s no cure, but you can help prevent the spread of the water mould: After visiting bushland, disinfect your shoes, tent pegs, bike and car tyres.

Pineapple with Phytophthora dieback

Phytophthora dieback

Phytophthora cinnamomi and other Phytophthora species

Considered a threat to Australian plant communities and the animals that depend on them, P. cinnamomi and a number of other Phytophthora species are major soil-borne pathogens of crops, forestry and natural vegetation, especially in southern Australia.

It has been distributed worldwide by man and globalisation; its initial spread is thought to have been via infected nursery and crop plants, which are still a means of transmission. It is also dispersed via seepage, drainage and irrigation water and via spread of infested soil on footwear, digging implements and tyres

Root rot is an unrelenting threat

When environmental conditions are not suitable for its growth, P. cinnamomi lies dormant, germinating and spreading when conditions improve.

In Australia Phytophthora food crop hosts include avocado and pineapple. It also occurs in other plant families, including Ericaceae, Eucalyptus, Proteaceae, Fagus, Juglans and Quercus.

Visit the Garden Explorer

Fungicidal drenches provide some resistance to root rot, but once the pathogen is in the soil, it isn't easy to be rid of.

Root rot

Water mould

Phytophthora dieback

Phytophthora is derived from the Greek word ‘Phyto’, meaning plant, and ‘phthora’, which means to decay, ruin or perish.

Phytophthora is a soil-borne water mould that thrives in soil and plant tissues. Infection usually leads to the plant’s death, and it is tough to get rid of once it’s in the soil.

Root rot symptoms include wilting, yellowing and retention of dried foliage and darkening of root colour.

There are areas in the Botanic Gardens that harbour the pathogen, and horticulturists regularly test the soil to determine areas of concern.

Pineapple plants are susceptible to Phytophthora

Garden Sign Story – Phytophthora dieback

Last survivor of an ancient line, the Wollemi Pine is an enduring link to Gondwana. Now it’s under threat.

Plant Pandemic

Death stalks Australia’s forests: Phytophthora means ‘plant destroyer’ and this introduced water mould lives up to its name. It travels through soil and water, infecting plants through their roots.

It is deadly, but there’s still hope. Our expert plant pathology team is working to protect Australia’s plants from disease. Years of research and testing have identified the best way to apply Phosphonate; a cure that triggers the tree’s immune system to fight off the infection.

Conservation partners: National Parks NSW; Wollemi Pine Recovery Team; Australian Institute of Botanical Science.

Image caption: Plant pathology team member Maureen Phelan painting Phosphonate onto Wollemi Pine bark, testing to find the most effective dosage.

Photo: E. Liew

You’re my hero

You can stop the pandemic in its tracks! Before and after a bushwalk, the simple act of cleaning your shoes and spraying them with disinfectant will work wonders.

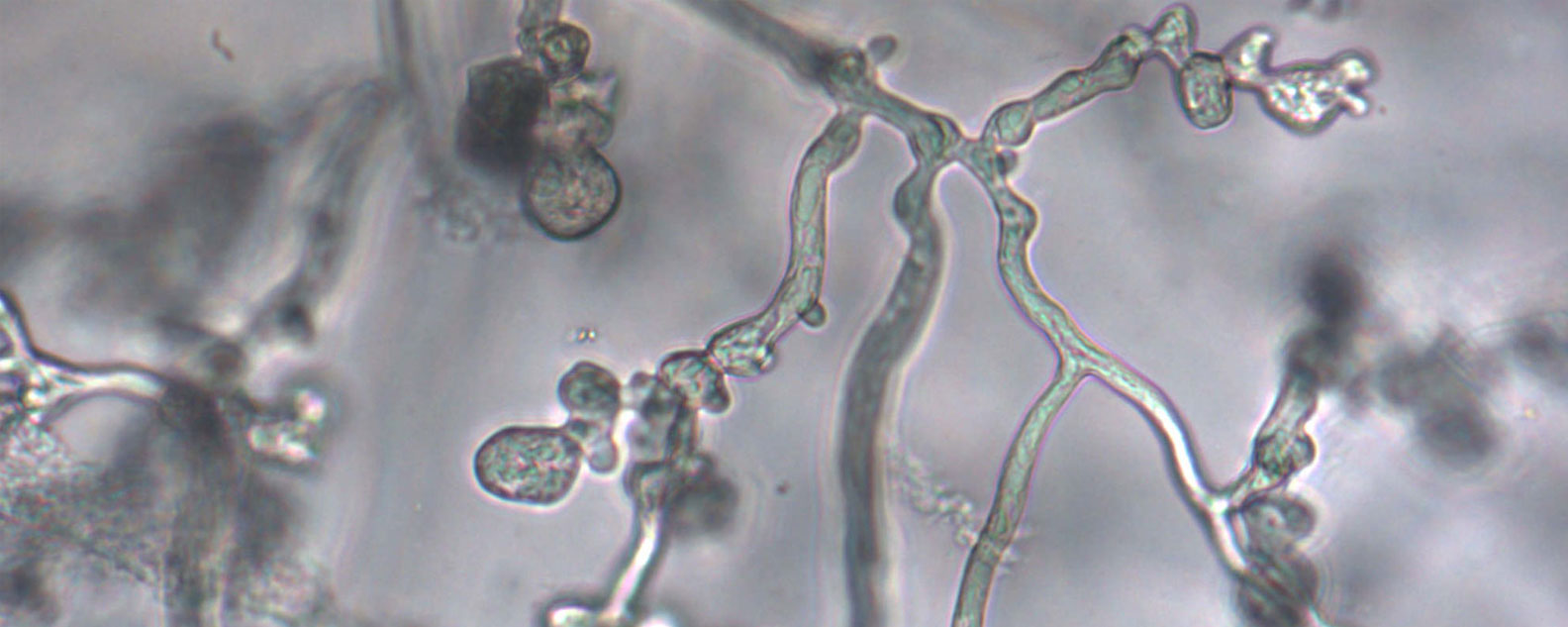

Image caption: Phytophthora cinnamomi is microscopic, spreading through waterways and soil transfer on shoes, tent pegs, gardening tools, bike and car tyres.

Photo: S. Bullock

Myrtle Rust on a Lilly-pilly

White Myrtle

A White Myrtle naturally resistant to Myrtle Rust – Rhodamnia argentea

The White Myrtle(Rhodamnia argentea) is a member of the Myrtaceae family with some natural resistance to Myrtle Rust, a devastating fungal disease. This resistance may prove significant in informing treatments for other species in the fight against Myrtle Rust.

Silver Myrtle

Brown Malletwood

Silver Malletwood

White Turpentine

Rhodamnia argentea is derived from the Greek word “rhodamnos” for a young branch, which references the tree’s slender branchlets, and the Latin word “argenteus” means silver.

The White Myrtle is found growing to 30 metres high in rainforest areas north of the Hastings River in New South Wales to Bowen in Queensland.

The White Myrtle has papery bark, flowers that grow in clusters of three and shiny red/black berries that grow to 10 mm and contain yellow seeds. It has whitish hairy branchlets and glossy oval leaves with dull, silvery-white undersides. The tree flowers from late Spring to Summer (mainly November and December on the east coast of Australia), and the berry ripens from February to March.

A Rhodeamnia argentea in flower

Garden Sign Story – Myrtle Rust

Australia’s iconic forests are in danger. An exotic fungus is spreading fast, and we’re working against the clock to fight it.

Fight the fungus

Yellow pustules of Myrtle Rust (Austropuccinia psidii) smother soft new growth, killing fully-grown trees. Rainforest myrtles are particularly vulnerable: Some species are close to extinction, and so far there’s no cure.

This graceful rainforest tree, Silver Myrtle (Rhodamnia argentea), has a natural tolerance to Myrtle Rust. How does it fight the disease? Dr Jason Bragg is studying its DNA to unravel the mystery. He hopes to find a way to boost resistance in other related trees.

Image caption: Jason with another iconic tree affected by Myrtle Rust: Broad-leafed Paperbark (Melaleuca quinquinerva).

Photo: L. Schwanz

Depending on Eucs

The ‘mewing’ call of Green Catbirds echo through Australia’s east-coast forests. Like Regent Honeyeaters and many other birds, they depend on the flowers and fruits of the Eucalyptus family.

Image caption: Green Catbirds (Ailuroedus crassirostris) are a type of bowerbird.

Photo: S. Mantle FLICKR

Bacterial Leaf Scorch on an olive tree

Bacterial Leaf Scorch

Xylella fastidiosa – a bacterial pathogen that causes yellow leaves

Xylella fastidiosa damages ornamental and fruit trees, and although it’s not present on Australian shores if it arrives, it poses a severe threat to our almond, macadamia, and pecan industries.

It is a bacterial pathogen transmitted by sap (xylem)-feeding insects, mainly from the Cicadellidae family. Xylem transfers water and nutrients from a plant’s roots to its stems and leaves. Species in the Cicadellidae family include leafhoppers, sharpshooters, froghoppers, and spittlebugs.

Bacterial Leaf Scorch

Golden Death

Phony Peach Disease

Pierce’s disease when found on grapevines – the disease’s name differs depending on the host plant it is affecting.

The pathogen’s genus name Xylella is a reference to its transmission of bacteria via the plant’s xylem. Xylem is derived from the Greek word ‘xylon’, which means “wood”, and is the most well-known xylem tissue.

Native to the Americas, Xylella fastidiosa travels on infected plants or insects. It has spread to Europe and was recently found in Italy and France. It has also been detected in the Caribbean, Taiwan, Iran, Turkey, Lebanon and Kosovo, and there have been unconfirmed discoveries in India and Morocco.

The number of plant species that can be affected, with or without visible symptoms, makes Xylella fastidiosa an incredibly invasive pathogen. Potential hosts include:

Golden wattle

Big leaf maple

Scotch broom

Green couch

Duranta erecta

Fuchsia

French broom

English ivy

Hydrangea

Sweet marjoram

Evening primrose

Sycamore

California wild rose

Blackberry

Rosemary

Stone fruit, including plums and peaches

Citrus.

Symptoms vary depending on the host species and the extent of the Xylella infection. They are usually associated with water stress and can include the browning of leaves with the veins turning yellow and wilting, eventually dying and dropping off the plant.

It is not present in Australia, but if it were, the significant Oriental Garden specimens and many other species in the Living Collections would be at risk.

A Golden Wattle in flower

Garden Sign Story – Xylella fastidiosa

Spring without blossoms, or autumn without colour – unthinkable! But now a global disease threatens plant species, including cherries and maples.

Image caption: Not just beautiful, Taiwan Cherry flowers are the main food source for Taiwan Yuhinas during their breeding season.

Photo: AWAI Shutterstock Id 783352681

Super-spreaders

Many of the world’s most loved ornamental trees and fruit trees are under attack. First detected in the Americas, the bacteria Xylella fastidiosa has now spread through Europe, the Middle East and parts of Asia.

Just like mosquitoes transfer diseases, sap-sucking insects spread bacteria between plants. They are big eaters – flying between plants and slurping hundreds of times their own body weight in sap every day.

Image caption: In North America, Glassy-winged Sharpshooters drink sap so fast they also pee constantly, tiny droplets falling like rain on unsuspecting passers-by.

Photo: Russ Ottens/University of Georgia/Bugwood.org

Plant quarantine

Keeping the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney disease-free is a challenge. All new plants are isolated for several weeks in our Nursery, where we monitor for symptoms and hitchhiking pests.

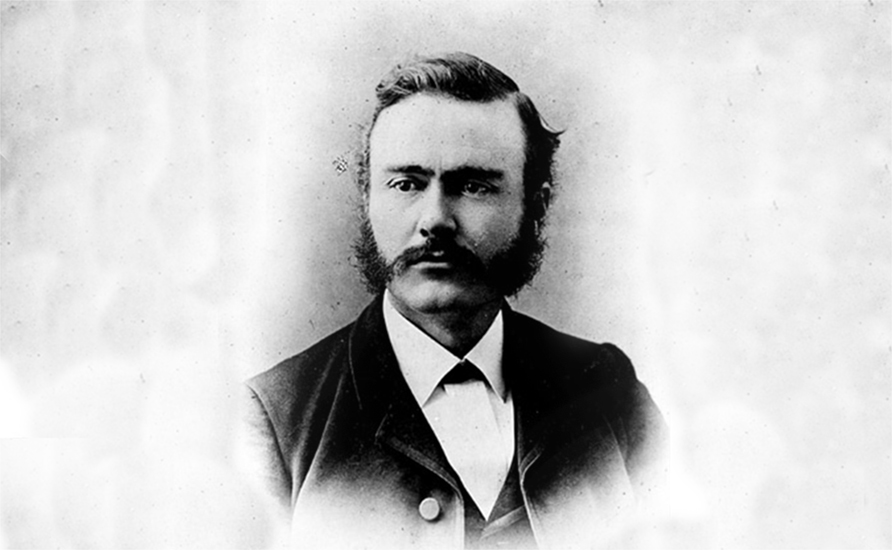

Pierce’s Disease is named after Newton Pierce

Pierce’s Disease

Xylella fastidiosa

Pierce’s Disease is a grape-specific bacteria spread by sap-feeding insects as they move from plant to plant, sucking and piercing foliage. After the insects have dined out on the leaves, the bacteria they’ve spread take residence in the plant, where it lives in the sap.

The bacteria blocks water and nutrient-carrying vessels, and the plant attempts to defend itself by producing more sap, adding to the blocked vessels. This series of events causes the leaves to turn brown or ‘scorch’, stunts the roots, causes dieback and then death.

Pierce's Disease has no cure, and if it arrives on our shores, it is a potential threat to grapes and viticulture. We have border controls, including plant quarantine and biosecurity measures to prevent its entry into the country.

Pierce's Disease was named for Newton Pierce, one of the United States’ first formally trained plant pathologists. Pierce’s descriptions from the late 1800s became the key symptoms that are used to identify the disease today.

X. fastidiosa occurs globally, and its worst effects are felt in riparian habitats along river margins and banks.

It was first described in California in the 1880s as a new disease of grapevines that eliminated viticulture. It took another 80 years to detect the bacterium that caused the disease.

It has as many as 600 host species in 85 plant families. The most susceptible are grape vines, oleander and almond trees.

Xylella fastidiosa symptoms depend on the species of host plant affected. In grapes, it is known as Pierce’s Disease, and its symptoms are:

Fruit: abnormal shapes, mummification and small fruit

Leaves: abnormal colours, forms and patterns, necrotic areas, yellowed or dead leaves

Roots: reduced and stunted roots

Stems: dieback, discoloured bark, internal discolouration, stunting

Whole plant: stunted growth, plant death, dieback.

It is not present in Australia, but if it were, the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney's significant HSBC Oriental Garden specimens and many other species in the Living Collections would be at risk.

Pierce's disease on grapes

Garden Sign Story – Pierce's Disease

Attacking grape vines from California to Europe… Pierce’s Disease is a serious threat to wine production, and it’s heading our way.

Image caption: Grape leaves showing symptoms of Pierce’s Disease, caused by the bacteria Xylella fastidiosa.

Photo: E. Mazzoni Alamy

A new threat

A new threat for Australia, these bacteria (Xylella fastidiosa) aren’t fussy. They attack a wide range of important agricultural crops including grapes, olives and stone fruit.

Easily spread by sap-sucking insects, the bacteria reproduce quickly inside the host plant. They invade stems, roots and leaves, blocking water and nutrient flow. Infected plants show symptoms like browning and withering leaves, stunted and misshapen fruit. Death occurs within two-three years, and there is no cure.

Image caption: Xylella fastidiosa has killed thousands of olive groves in Southern Italy.

Photo: C. Palma Shutterstock

Border control

Quarantine is one of the most important defences against biosecurity threats. You can help protect Australian agriculture and our natural ecosystems by declaring all plant material at the border.

Yellow Dragon Disease on citrus

Yellow Dragon Disease

Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus, a bacterial infection in Citrus trees

Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus, or Yellow Dragon Disease, is one of the most dangerous citrus diseases globally.

Caused by a bacterial infection, Yellow Dragon Disease spreads via small insects known as psyllids that carry the disease from plant to plant. It affects citrus in the Rutaceae family, and different species of citrus have different levels of susceptibility.

The symptoms include small, yellow, mottled leaves with blotching, yellow shoots, enlarged and corky leaf veins, and small and distorted fruits.

There is no cure for Yellow Dragon Disease. At the time of writing, it has not been found in Australia.

Yellow Dragon Disease is found globally, including in Africa, Asia, Europe, North America, Oceania, and South America.

Citrus Tree Diseases in Taiwan, India and the Philippines

Some citrus’ are more affected by Asian Greening than others. In Taiwan, India and the Philippines, sweet orange (Citrus sinensis) and mandarin (C. reticulata) are the most susceptible to Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus, with lime (C. aurantiifolia), lemon (C. limon), sour orange (C. aurantium) and grapefruit (Citrus x paradisi) showing more tolerance. In India rough lemon (C. jambhiri), sweet lime (C. limettoides) and pomelo (C. grandis) are tolerant, and the trifoliate orange (Poncirus trifoliata) is fairly tolerant.

Native habitat

Also known as Huanglongbing and Asian Greening, Yellow Dragon Disease is present in the agriculture/ horticulture industries, in glasshouse production settings, managed forests, plantations, orchards and grasslands. It mainly affects the Rutaceae family and is considered invasive due to the cryptic nature of the disease and the ease of its spread.

Yellow Dragon Disease is a bacterial pathogen that infects all stages of the citrus life cycle from flowering, fruiting, seedling, and vegetative growth.

It moves from plant to plant via insect psyllids' sucking and piercing mouthparts. There are no chemical controls that specifically target the bacterium.

China and Indonesia manage the disease by eradicating infected plants and hosts, producing and planting disease-free trees and using chemicals to control psyllids.

The parasitic wasp Tamarixia radiata has shown success as a biological control. The wasps lay eggs in psyllids, and as they develop and hatch, the larvae consume the psyllid from the inside out.

Managing bacteria, drenching seedlings, employing good sanitation and nursery hygiene protocols, removing infected plants and keeping plants in good health is the best defence against this pathogen.

One of the reasons that Yellow Dragon Disease is so dangerous is that host plants can be without symptoms for up to three years before showing signs of infection.

The first symptom is usually yellow shoots on a citrus tree. The entire canopy yellows, showing symptoms of zinc or manganese deficiency or blotchy mottling, and it reduces in size. Blotchy mottle is the most characteristic symptom but is not specific to Yellow Dragon Disease.

Chronically infected trees have minimal leaves and extensive twig dieback. Their fruits are often small, crooked, have a sour or bitter taste and are poorly coloured (the origin of its common names: Yellow dragon/Asian Greening). Distorted shrunken fruits often contain aborted seeds.

When scientists classify bacteria, Candidatus is put before the name of a bacterium that cannot be grown in culture. Liber refers to the interior bark of plants, which is found next to the wood. Bacter is derived from the Greek word bacterion which means 'small staff' and is linked to ‘baktron’ which means “stick, rod, staff or cudgel”, describing the first bacteria that were observed, which were rod-shaped. Asiaticus is from the Latin word meaning a native of Asia or occurring in Asia.

Yellow Dragon Disease

Asian Greening

Huanglongbing (Mandarin)

The disease is not present in Australia. Our island continent has protected us so far from this invasive plant pathogen.

Tamarixia radiata and Citrus Psyllid

Garden Sign Story – Yellow Dragon Disease

Huánglóngbìng (Chinese), Yellow Dragon Disease, Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus

Citrus fruit is one of summer’s sweetest pleasures. But Yellow Dragon Disease is on the rise, killing and stunting citrus across the globe.

Sour story

Yellowing leaves and stunted fruit are early warning signs, and many plants infected by the bacteria (Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus) will die. Luckily some citrus, including lemons, grapefruit and sour oranges, are able to tolerate the disease.

A nasty trick helps the disease spread: It’s carried by psyllids – tiny sap-sucking insects – and the bacteria can hide inside them for three months. So far, Australia’s quarantine controls have stopped both infected plant material and psyllids.

Image caption: Sweet orange infected with Yellow Dragon Disease. Photo: H.D. Catling Bugwood.Org

Eaten alive

Parasitic wasps are a grisly but effective biological control! Female wasps lay eggs on psyllids, which are then devoured by the wasp larvae.

Image caption: 1 mm Tamarixia radiata wasps laying their eggs on psyllid larvae.

Photo: US Dept. Of Agriculture

Send your samples to PlantClinic

The PlantClinic at The Royal Botanic Garden Sydney is able to diagnose the plant diseases that threaten our forests, parks and gardens.