New genomic research highlights Indigenous ecological knowledge

A collaborative cross-cultural research team have discovered that movement of the culturally significant Bunya Pine by Indigenous Peoples varied among regions and intensified in south-east Queensland to maintain cultural connectivity following European colonisation.

A collaborative cross-cultural research team have discovered that movement of the culturally significant Bunya Pine by Indigenous Peoples varied among regions and intensified in south-east Queensland to maintain cultural connectivity following European colonisation.

The giant Bunya nuts contained in heavy cones have also held both cultural and culinary significance for Aboriginal Australians for thousands of years.

How genomic tools provide insight into plant dispersal

Genomic tools are helping to retrace past Indigenous dispersal of plants and The Research Centre for Ecosystem Resilience (ReCER) at the Botanic Gardens of Sydney and their collaborators are at the forefront of a new wave of cross-cultural studies providing insight into how first Australians shaped the distribution of many plants. Head of ReCER, Professor Maurizio Rossetto, says these studies provide insights into how first Australians shaped the distribution of many plants.

“We are increasingly aware that what we thought of as ‘wild’ ranges of species did not take into account traditional indigenous activities,” Maurizio said.

“Indigenous Peoples have manipulated environments and species for millennia. However, conservation and restoration science often overlook ancient human plant dispersal," he said.

By developing collaborations with Indigenous people, Maurizio, ReCER research fellow Monica Fahey, Masters student Patrick Cooke and cross-cultural ecologist Emilie Ens of Macquarie University have been able to combine oral histories, Indigenous knowledge, and scientific data to unravel how the histories of Australia’s plants and people are often closely intertwined.

The team’s research into the ancient human dispersal of the Black Bean tree (Castanospermum australe) revealed its unexpected distribution pattern is the result of humans deliberately dispersing this tree to new places. By combining the genetic information with Indigenous knowledge, the cross-cultural team revealed that the tree’s dispersal, as told by its genetics, is compatible with the traditional songlines and walking tracks that local First Nations peoples have travelled for thousands of years.

The research team, in collaboration* with cultural heritage consultant Ray Kerkhove from the University of Queensland, decided to continue their contribution to the ‘Indigenous agriculture’ debate by sharing insight into human dispersal of the Bunya Pine in a recently published article in People and Nature Journal.

*Collaborators include: Oliver Costello (Jagun Alliance), Gerry Turpin (Tropical Indigenous Ethnobotany Centre), Ray Kerkhove, and Philip Clarke (South Australian Museum).

DNA from Bunya Pine leaf samples revealed differences in the way First Nations people shared nuts across regions and following European colonisation. Credit: Emilie Ens

Retracing the dispersal of Bunya Pine

The Bunya Pine (Araucaria bidwillii) is a culturally and spiritually significant conifer tree for several Indigenous groups in eastern Australia. Sharing the edible nuts and attending ‘Bunya gatherings’ is an important way for these groups to maintain kinship and cultural connections, often transporting the nuts long distances.

Lead author of the recent study is Monica Fahey from Botanic Gardens of Sydney's ReCER team. She says Bunya Pines grow naturally in two disjunct regions, in Southeast Queensland and over 1400 km to the north in the Australian Wet Tropics.

“We used Bunya leaf DNA samples to reconstruct the shared ancestry between trees within and between the two regions and to infer the historical movement of Bunya across the landscape. Oral history and Indigenous knowledge on the use of Bunya was used to interpret the genetic data,” Ms Fahey said.

Ms Fahey says a difference in historical dispersal of Bunya nuts between the two regions was detected.

“We identified genetic patterns that suggest a long-term absence of Bunya dispersal within the Australian Wet Tropics, where Indigenous knowledge of its use is limited, and extensive dispersal amongst sites in Southeast Queensland, consistent with oral histories and Indigenous knowledge about sharing of Bunya nuts across that area,” Ms Fahey said.

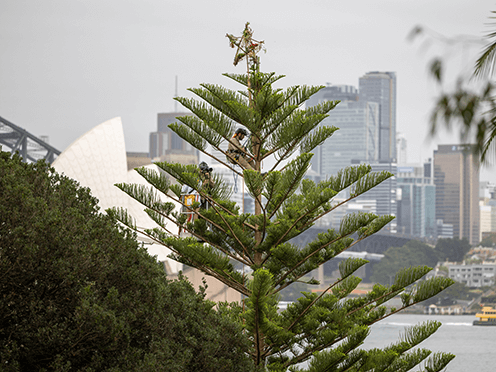

Collecting Bunya Pine leaf samples for genetic analysis. Credit: Emilie Ens

Genomic data reveals increased dispersal may be a response to colonisation

Ms Fahey says genomic data suggests Indigenous Australians increased sharing of Bunya to preserve culture following European colonisation.

“By analysing the data with and without sites that were established post colonisation we discovered evidence that Indigenous movement of Bunya Pine intensified following European colonisation,” Ms Fahey said.

“We concluded that pre-colonial movement was likely restricted by kinship-based custodial rights, and that when Indigenous Peoples were displaced by European settlers, movement and sharing was intensified to maintain cultural connectivity. For instance, Indigenous Peoples were known to plant Bunya when they were moved onto missions, or in collaboration with European settlers on homesteads,"she said.

Similar post colonisation long-distance dispersal of culturally significant plants has been detected in New Zealand and America, suggesting that increased dispersal may be a widespread Indigenous response to colonisation.

Biocultural restoration can help restore ecosystems and cultural connections

Biocultural restoration science is a relatively new research field that combines biological and cultural research to guide inclusive ecological restoration that restores not only ecosystems but also human and cultural relationships to place.

“Research into the historical dispersal of Black Bean, Bunya Pine and other culturally important edible species we are currently studying (e.g. Blue Quandong, Black Apple and Kurrajong) can help restore ecosystems and cultural connections,” Ms Fahey suggested.

“Translocation, or the movement of plant propagules from one place to another, is becoming an increasingly important tool in conservation, especially given the need to help species adapt to a changing climate. Our findings contribute to a broader understanding of the demographic and genetic impacts of translocations and can be combined with Indigenous knowledge to design a conservation strategy for Bunya Pine that incorporates both biological and cultural information,” she said.

To learn more about the ReCER team's work to restore Australia's unique habitats, check out the What the Flora!? episode below and subscribe to the Garden's YouTube channel.

Related stories

One year ago, a pungent princess captivated the world when she bloomed at the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney. Our new documentary goes behind the scenes to reveal her rapid rise to fame, her extraordinary life cycle, and the conservation work saving this once-a-decade bloomer.

Discover the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney's very own "Christmas trees" - a festive trio of pretty pines from a lineage stretching all the way back to the time of the dinosaurs.

For the team at the Research Centre for Ecosystem Resilience (ReCER), a request from the Blue Mountains Botanic Garden to design a hedge of the towering Nothofagus moorei, or Antarctic beech, sparked a unique collaboration between science and horticulture.