Hedging our bets

For the team at the Research Centre for Ecosystem Resilience (ReCER), a request from the Blue Mountains Botanic Garden to create a hedge of the towering Nothofagus moorei, or Antarctic beech, sparked a unique collaboration between science and horticulture.

What began as a practical garden upgrade has grown into a pioneering conservation project, blending genetics, ecology, and design to safeguard one of Australia’s most ancient and vulnerable trees.

Richard Dimon is a geneticist with the Research Centre for Ecosystem Resilience (ReCER), not a landscaper or horticulturalist. So, he was surprised when a request came from Ian Allan at the Blue Mountains Botanic Garden to design a hedge of Nothofagus moorei or Antarctic beech. “I wondered if it was a bit of a joke,” Richard says. “Antarctic beech is a cool temperate rainforest tree that can grow up to 50 metres tall. I wasn’t sure how realistic it was to use it in a hedge.”

But then Ian explained that the Garden already had a well-established hedge, planted as part of the original formal garden design in 1987, and were looking to upgrade it as part of a transition to ensure the garden grounds are a multi-purpose pleasure, conservation and research space.

“We had space at Mount Tomah to plant several new hedges as part of plans to replace cherry laurel hedges that now pose a locally significant weed risk in the Blue Mountains,” Ian says.

“Our existing Nothofagus hedge has great ornamental value, but from a conservation perspective it doesn’t achieve much because it was grown from cutting propagated clones of just two original wild seedlings collected in the Barrington Region. This means the conservation and genetic value is very low.”

Working in harmony

Serendipitously, the Mount Tomah and ReCER teams began investigating conservation options for Nothofagus moorei at a similar time, which meant there was a chance not just to sample the wild populations but to improve genetic representation in the ex-situ (away from the wild) conservation collection. The intention of the new collection was to use the plants not just as a hedge but for research, breeding, and in the long term, reintroductions or translocations if the wild populations declined.

Nothofagus moorei is a Gondwana relict species, now restricted to the cool temperate forest from southern Queensland (Lamington Mountain ranges) to the mid north Coast of New South Wales (Barrington Tops) at altitudes from 500-1550 metres. Many of the forests containing Antarctic beech were extensively logged in the early to mid-1900s meaning that wild plants are rare, and potentially quite inbred. As an International Union for Conservation (IUCN) vulnerable species, restricted to higher altitudes and mountain tops, climate change is already a concern, particularly for populations occurring at the highest elevation which may have nowhere left to inhabit.

“It can be difficult to assess how long-lived species, like Antarctic beech, are responding to climate change,” says Professor Maurizio Rossetto, head of the ReCER team. “This species can live for hundreds of years, and when we have many old standing trees, the species can appear healthy, but in reality they are an example of living dead; populations or species which are likely to disappear despite currently existing, as there isn’t a next generation growing and then producing fruit.”

Professor Rossetto says long-lived species such as Nothofagus moorei might only recruit or produce the next generation every 50 to 100 years. This is far longer than our current monitoring lifetime. Combining genetics with surveying for multiple age classes in the wild can help researchers understand which populations are at risk of decline, as well as prioritising locations to collect material for inclusion in an ex-situ conservation collection.

From forest to lab

Working together, the Botanic Gardens and NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service teams undertook field surveys led by Dr Colin Bale to sample plants across the range and within localised populations of Antarctic beech. They took over 400 samples for genetic analysis, across 80 populations, spending more than 18 days in the field. Their aim was to identify which populations were possibly in decline, which were healthy, and which plants could be collected from each region to ensure that the entire genetic diversity of the species was represented.

Like many of the ReCER projects, Richard’s analysis used Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) to detect differences in common alleles which signify shared ancestry or relatedness between plants.

“We found that the results broadly matched the natural geographic separation of the four main remaining regions; Border Ranges, Dorrigo Plateau, Barrington and Werrikimbe-Comboyne, but with evidence of historic mixing between them,” Richard explains. “Interestingly, we observed that the closest geographic regions are not the closest genetically, with the Border Ranges and Comboyne being more genetically similar than the geographically closer Barrington and Comboyne. All populations north of the Manning River are more closely related than populations south of the Manning River.”

Richard theorises that this discrepancy is likely a reflection of the changing climate and habitat over the millennia when the species had a much wider distribution. As the suitable habitat range has contracted to mountain-top refugia, geneflow between populations has reduced, and the separation of the Barrington Ranges has acted as a physical barrier to pollen or seed movement. This data helps plan strategic breeding or pollinate between populations to help introduce new genotypes and, potentially, improve resilience in a changing climate.

Using an in-house developed method to select unique genotypes which represent over 90% of each region’s genetic diversity, Richard identified approximately 25 plants from each of the four main regions which should be included in the conservation hedge program at Mount Tomah. These 100 plants could then be duplicated as insurance collections across other botanic gardens and institutions.

“Receiving this very specific type of guidance about what plants to collect and from where, enables us to design a targeted collection of wild cutting material, as well as plan for alternating genotypes in the hedge,” Ian says.

Safeguarding the future

Ian led the collections of roughly 100 target plants from each of the four regions from spring 2024 to summer 2025, and will begin growing the plants, using clonal propagation. “This species actually coppices too, so growing it from cuttings is quite easy, but Richard’s guidance makes sure we don’t inadvertently collect wild clones or close relatives,” Ian says.

Cuttings are currently being propagated at the Blue Mountains Botanic Gardens, and the new hedge is planned for installation in the coming years as soon as enough material has been propagated. There are also plans to increase diversity in existing naturalistic groves that were heavily impacted by the 2019 bushfire, that burned part of the Garden’s living collection. This method is not exclusive to Antarctic beech and is actually suitable for many species.

“Contrary to expectations many rainforest species are actually suitable for hedging.” says Ian. “As a hedge these plants can be used for conservation and research purposes in small spaces without relying on the infrastructure to maintain plants in pots or the large space required to accommodate 50-metre-tall trees.”

Over the long term, this collection will also form part of a dispersed meta-collection shared across gardens in New South Wales, replicating similar models developed for the Wollemi Pine (Wollemia nobilis) and, more recently, the Dwarf Mountain Pine (Pherosphaera fitzgeraldii). This project is also contributing to a global Nothofagus conservation program.

Meet the ReCER team

Led by Professor Maurizio Rossetto, ReCER’s passionate team uses science and innovation to protect Australia’s wild heritage for generations to come.

Tucked within the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney is a powerhouse of scientific innovation – the Research Centre for Ecosystem Resilience (ReCER). Established around four years ago, ReCER grew from the Gardens’ former Evolutionary Ecology research group to meet the urgent need for large-scale, genetics-driven conservation.

Professor Maurizio Rossetto, Head of the Research Centre for Ecosystem Resilience, who has worked at the Gardens for more than 23 years, leads the centre and has been instrumental in shaping its direction. “I’ve always been researching how DNA can inform the management of biodiversity,” he explains. “Understanding how native species are distributed and assembled helps us not only understand natural landscape processes but also support improved biodiversity management strategies.”

At its core, ReCER uses advanced genomic tools to understand and restore Australia’s unique plant communities. By studying the genetic makeup of species, the team can identify how plants adapt to changing conditions and guide restoration projects that promote resilience and diversity. “Our focus is on developing the tools that allow us to support threatened species and restoration programs directly,” says Maurizio. “We provide guidance to ensure populations are genetically viable, whether that’s helping reintroduce rare plants or advising on how to build resilience against diseases like myrtle rust.”

ReCER’s applied science is transforming how restoration and recovery are planned across New South Wales. The team of around twenty scientists – all geneticists – collaborates with land managers, government agencies, and conservation partners to translate complex data into on-ground action. “All that we do has direct applications,” Maurizio says. “Every project is aimed at ensuring species not only survive now, but are equipped to thrive in the future.”

When Maurizio first led the research group, there were only three scientists. In just a few years, the team has grown exponentially. “There’s increased recognition for the type of work we do,” he notes. “No one else in Australia, and few internationally, operate at the scale we do.” That scale has attracted collaborations across Australia and beyond, with ReCER now partnering with other states and international research groups seeking to replicate its model of genomics-driven conservation. “We’re seeing our work being woven into new biodiversity legislation and policy development,” says Maurizio. “The more we can influence policy, the greater our impact.”

While most of ReCER’s projects are governmentfunded, community support plays an important role. Foundation & Friends of the Botanic Gardens have provided vital assistance, funding the laboratory equipment that underpins the team’s cutting-edge research. “Foundation & Friends funded all of our lab equipment,” Maurizio explains. “And through them, we’ve also had generous donors come forward to support specific projects – such as our new marine work on mangroves and salt marshes.”

Such partnerships show how philanthropy and science can come together to safeguard ecosystems for future generations.

Acknowledgments

This work could not have been achieved without the support of Dr Colin Bale, Adam Fawcett Tricia Waters, and staff of the National Parks and Wildlife Service NSW who in partnership with the Botanic Gardens of Sydney staff, have helped collect leaf and propagation material across the populations.

This story was originally published in The Gardens, the quarterly magazine of Botanic Gardens of Sydney.

Get it delivered to your door by becoming a member. Published four times a year and aligned with the seasons, the 36-page print magazine balances expert insight with accessible, engaging storytelling, offering members a deeper connection to one of Australia’s most loved public institutions.

Enjoy discounts, exclusive events and experiences, and the knowledge that you are part of a passionate community making a difference.

Related stories

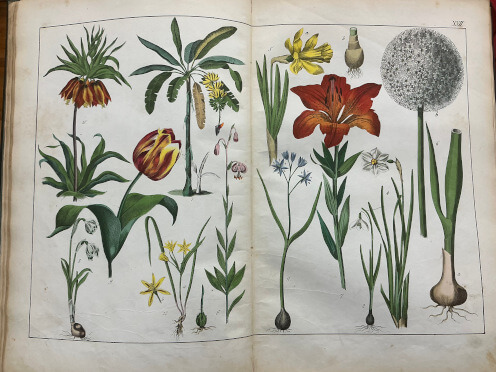

As fascinating as the books housed at the Daniel Solander Library are, the journeys they have taken to arrive there can be just as intriguing, writes Miguel Garcia.

With a fresh new look and a renewed sense of purpose, Growing Friends Plant Sales continues to go from strength to strength, uniting passionate volunteers, beautiful plants and a shared love of the Gardens.

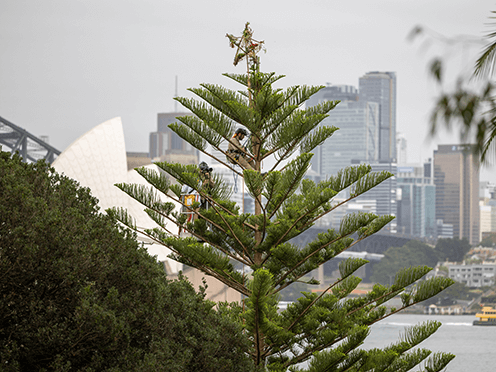

Discover the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney's very own "Christmas trees" - a festive trio of pretty pines from a lineage stretching all the way back to the time of the dinosaurs.